As the world reels from the recent impact of COVID-19, researchers are examining ways that the past can inform current and future pandemic response. The most widely documented historic pandemic is that of the Spanish flu in 1918, and while a different set of viruses means drastically different outcomes, comparing and contrasting past and present scenarios provides helpful insight into counteracting viral threats and coordinating global mitigation.

Though the SARS-CoV-2 virus (which causes COVID-19) is straining global resources, its rate of mortality is actually far lower than that seen in cases of exposure to some other influenza viruses. The Spanish flu pandemic affected a staggering number of global citizens, with more than 50 million deaths documented worldwide. Nowadays, access to modern therapeutics and seasonally effective vaccines reduces potential mortality posed by viral infection, and yet the current COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates humans’ continuing vulnerability to as-yet unidentified viral strains, especially from quickly mutating viruses such as influenza.

So, how can measures enacted more than 100 years ago inform the way we address a modern pandemic? Following are some of the insights that researchers have gleaned.

Sharing data is essential. At the time of the outbreak of Spanish flu, the world was at war. This greatly limited the reporting of information regarding the pandemic. Citizens were often entirely unaware of the virus until it was too late. Response was reactive, and limited to specific geographic communities; only localized precautions were taken, and this allowed the virus to spread quickly throughout the globe.

Though modern access to technology supports information sharing through global media, insufficient information, as well as misinformation, abounds. The need for effective sharing of information between government entities and research institutions worldwide has been highlighted by the current outbreak of COVID-19, making clear that coordinated provision of accurate, informed data to the public will be essential to any future pandemic response.

Public health systems must be supported. Many of the world’s public health systems were developed partially in response to the impact of the 1918 pandemic. Prior to the Spanish flu, epidemiology was still a fledgling effort, and standardized responses to public health threats were not yet formulated.

Though the world has made significant progress in these fields, COVID-19 has revealed glaring inadequacies in public health systems worldwide. Shortages of protective gear such as masks and gloves, limited availability of life-saving equipment, and lack of information regarding potential treatment have left many locations straining under the burden of treating admitted patients—all problems that, going forward, must be proactively addressed.

Preventive measures aid containment. In 1918, there was no go-to plan or methodology for containing a pandemic, and the world was taken completely by surprise. While some municipalities issued orders for mitigation similar to those enacted to address today’s pandemic (including closing schools, banning public gatherings, issuing isolation orders and advocating for use of masks), these measures were not coordinated or widespread. World War I was still underway, and the mobilization and movement of troops created ideal circumstances for viral spread: overcrowding, close contact, and travel through geographically and ethnically diverse locations.

Early response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been critical to mitigation. Hastily enacted travel restrictions served to slow viral spread, despite their haphazard and sometimes confusing implementation. Shelter-in-place, social distancing and public education initiatives have proven reasonably effective at “flattening the curve.” Still, there is plenty of room for improved coordination not only between national, state and municipal leaders, but worldwide. A global playbook for swift, coordinated pandemic response (replete with coherent, detailed best practices for containment) is a must for limiting future viral threats.

Ongoing vigilance will be critical. The Spanish flu was persistent. Its second wave was the deadliest, decimating the global population in the autumn of 1918 before resurging again in the winter of 1919. As we cross the threshold of COVID-19’s first year, we must keep our wits about us if we wish to avoid a similar fate. Experts are already reporting the presence of COVID-19 mutations, producing strains that may prove more deadly or more easily transmissible than their predecessors—which means we must maintain our current vigilance.

Modern medicine makes a huge difference. Nonpharmaceutical methods proved ineffective in preventing Spanish flu death victims. In lieu of effective medicinal treatment, the use of nonpharmaceutical methods meant that many victims of the 1918 pandemic succumbed not to the virus itself, but to secondary bacterial infections. Antibiotics were not yet available—penicillin was not discovered until 1928. Those with already compromised immune systems were exceedingly vulnerable, but even seemingly healthy individuals (including those in the younger population, age 20–40) died, often from cytokine storm, a massive overreaction of the immune system that leads to systemic inflammation.

Today, we are able to limit deaths from COVID-19 with complex, multipronged treatment that can include the use of antivirals, corticosteroids, convalescent plasma, oxygen therapy and ventilation. Still, there is no known cure for COVID-19, and though several recently developed vaccine candidates appear promising, they lack the ability to combat alternative strains of SARS-CoV-2 and may lose efficacy against future variants.

Testing and tracing efforts must be expanded—and coordinated. Proactive testing, advanced diagnostics and contact tracing technology were not available in 1918. But they are today, and these methods can help researchers identify and contain active infections quickly and effectively. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) and its Collaborating Centers for Reference and Research on Influenza are connecting researchers and contact tracers in more than 114 member countries. This enables researchers around the globe to share analytical data and specimens collected from patients anywhere in the world, allowing them to collaborate and coordinate their efforts.

Expansion of viral surveillance and preventive testing within the world’s most vulnerable populations is an important part of pandemic preparedness. When proactive, accessible testing is paired with ongoing, strategic attention to genomic research, it empowers humanity to react swiftly to future viral threats.

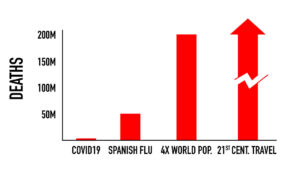

Proactive vaccine development is a global need. The threat of another global pandemic is not just a threat to one nation or way of life—it endangers all of humankind. The Spanish flu of 1918 wiped out more than an eighth of the global population; a pandemic of that magnitude today would mean the loss of more than 200 million lives.

Experts worldwide agree that vaccine development is the best way to prevent or stop a pandemic. But it is also time-consuming, complex and costly. While development of a universal vaccine for type A influenza by scientists at the leading edge of pharmaceutical and viral research is already underway, support of those efforts must be sustained.

If we wish to ensure humanity’s ability to both survive and thrive, history tells us we must organize and unite researchers and governments worldwide against a common enemy—the threat of the next viral pandemic.