Thanks to Al Gore, Greta Thunberg and myriad unnamed scientists and researchers around the world (who have labored for decades to raise awareness), most global citizens are now aware of climate change, and the catastrophic effect of human behavior on our natural environment. What most have not considered until recently, though, is those changes’ role in increasing zoonotic illnesses, driving the spread of pandemic disease.

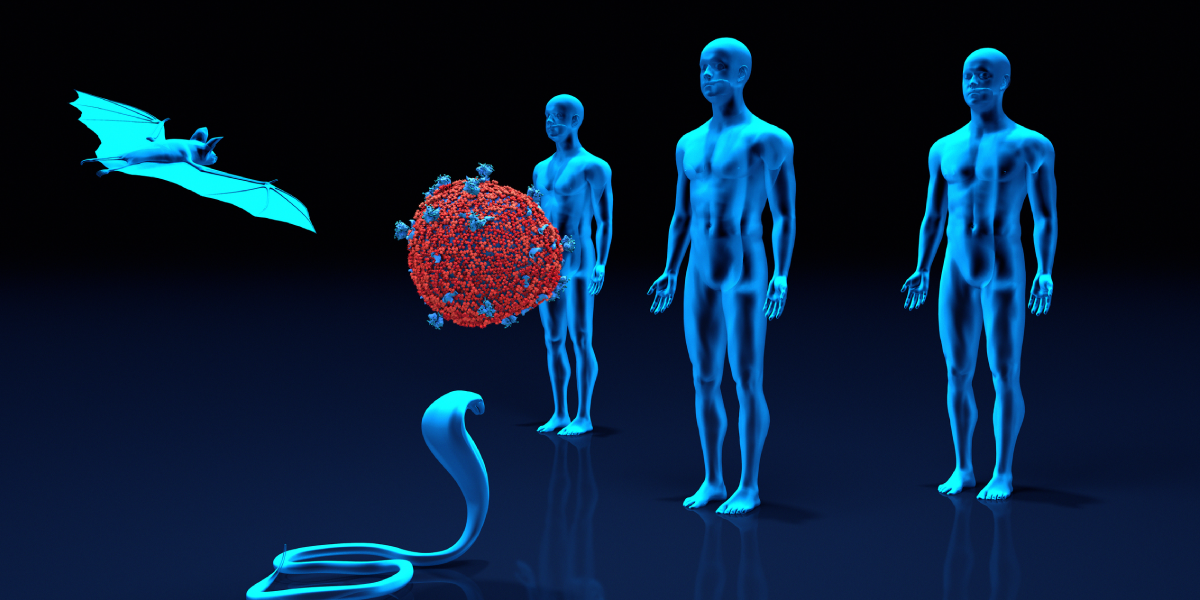

Zoonotic illnesses are diseases caused by viruses that cross the animal–human divide, jumping from infected animals to people. When certain animal hosts (such as bats, pigs, rodents and birds) live in close proximity to humans, viral mutations can occur that enable transmission between species. The result? Virulent strains to which humans have little immunity, driving viral spread that can quickly grow to pandemic levels.

Catastrophic elimination of biodiversity and the ongoing destruction and loss of animal habitat have created hotbeds of zoonotic illnesses. When combined with global changes in weather and temperature patterns that determine species migration and breeding habits, new opportunities are created for contact between previously separated species—and viral spread.

All parts of our planet are increasingly interconnected, and failing to recognize that drivers of climate change can also drive viral spread could cripple efforts to prevent future pandemics. Even a small and subtle change to an ecosystem can trigger a domino effect that increases the risk of zoonotic illness, or furthers the reach of future pandemic disease.

Deforestation, which occurs routinely for agricultural purposes, is an excellent example: loss of habitat for native species means they must find new territory, often placing them in close proximity to humans, agricultural animals or other previously foreign species of wildlife, and thus creating new avenues of pathogenic contact. Exposure to modern agricultural centers increases the risk of transmission from wildlife to livestock (and, in turn, to agricultural workers).

There are already many examples of zoonotic illness caused by climate change–driven viral spread:

Hantavirus. First identified in Panama in 1999, hantavirus (estimated mortality rate: 52%) made the jump from infected rats to humans after the rodent population exploded due to increased rainfall and elevated temperatures caused by climate change.

Ebola. The 2014–2016 outbreak of Ebola virus originated in a rural area of Guinea. Extreme deforestation (resulting in an estimated 80% loss of habitat for native wildlife) placed human residents in close contact with native bat species. Patient Zero was a toddler who was inadvertently exposed to guano from infected bats, while playing in a hollow tree.

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Identified first in the Arabian Peninsula, MERS made the jump from habitat-encroached bats to camels kept for agricultural purposes, before infecting the humans who tended them and consumed their milk. It then spread from rural populations to more urban areas via exposure of healthcare workers to infected individuals, as well as tourists returning to their countries of origin.

SARS-CoV. Illegal trade in endangered wildlife contributed to the viral spread of SARS-CoV in 2004. This virus made the jump from captive civets held for sale as exotic pets to humans, killing approximately one in 10 of those infected.

Even SARS-CoV2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has been linked to climate change, with climate-driven loss of habitat resulting in a geographic concentration of bat species known to carry coronavirus. According to researchers at Cambridge University, a concentration of previously separated bat species within certain areas of Southeast Asia led to an increased concentration of coronavirus variants. This, in turn, enabled the zoonotic transmission to humans responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers estimate that 60% of emerging human pathogens are zoonotic diseases arising from contact between humans and animals that is intensified by global climate change. But it doesn’t stop there: human activity is further increasing viral spread by delivering pathogens to new and exotic destinations. This is especially evident in the proliferation of vector-borne illnesses (those carried by mosquitoes, fleas and ticks) in previously unforeseen areas. Outbreaks of dengue fever in New York, Zika in Texas, and West Nile Virus in Florida are prime examples, and experts anticipate that these scenarios will become more common as changes in weather and temperature render carriers more effective over broader ranges.

As erratic changes in weather patterns and temperature become the norm, humans will need to adapt their behavior to survive. Thus far, we have made little global progress in addressing these issues. We must not only do our best to slow the progression of climate change and reverse its ongoing impacts on our environment; we must also make use of all available tools to increase our immunity to zoonotic threats.

This means shifting our approach to zoonotic disease from a reactive stance to a preventive one, drawing on the foundations of current research to develop vaccines and treatments that provide proactive protection against the most likely threats. By recognizing and admitting that the arrival of the next zoonotic disease is merely a matter of time, we can shift our attention and resources to preventing viral spread before it occurs.